The Rise And Fall Of Synthetic Food Dyes

Authored by Marina Zhang via The Epoch Times (emphasis ours),

In 1856, 18-year-old chemist William Henry Perkin was experimenting with coal tar-derived compounds in a crude laboratory in his attic.

His teacher, August Wilhelm von Hofmann, had published a hypothesis on how it might be possible to make a prized malaria drug using chemicals from coal tar, and as his assistant, Perkin was hoping that he would be the one to discover it.

The experiment was a failure. Rather than the prized drug, Perkin created a thick brown sludge. However, when he went to wash out the beakers with alcohol, it left behind a bright purple residue.

The residue became the world’s first-ever mauve synthetic dye.

Before the invention of synthetic dyes, people obtained dyes through organic materials such as plants, clay, minerals, or certain animals such as insects and squid.

Natural dyes such as those from clay tended to fade quickly, and those that were long-lasting, such as natural indigo dyes, required an arduous extraction process that made them expensive.

However, Perkin’s mauve dye was stable and easy to make.

Mauve dye became an instant hit in the UK and globally. Consumers were seized by “mauve measles.” Everyone wanted a piece of it, including Queen Victoria, a fashion icon at the time who ordered mauve gowns, hats, and gloves.

Perkin’s discovery and commercial success prompted chemists in Europe to find more dyes in coal tar; magenta was discovered in 1858, methyl violet in 1861, and Bismarck brown in 1863.

Synthetic dyes would soon be added to everything—clothing, plastics, wood, and food.

The rapid innovation was not without consequences. Many dyes were found to be harmful within decades of discovery. More than a century later, the United States recently announced the removal of synthetic dyes from food.

Dyes in Food

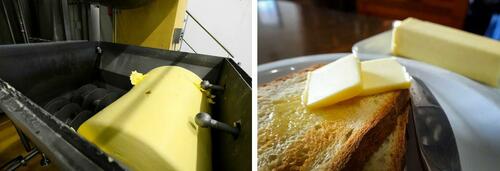

For centuries, people have colored food to make it appear more appealing. Butter, for example, is not always yellow. Depending on the cattle feed, breed, and period of lactation, the color of butter can fluctuate seasonally, from bright yellow in the summer to pale white in the winter.

“Dairy farmers colored butter with carrot juice and extracts of plant seeds, called annatto, to give them a uniform yellow all year round,” Ai Hisano, an associate professor at the University of Tokyo specializing in cultural and business history, wrote in the Business History Review.

Natural colors, unlike artificial ones, are susceptible to changing pH, temperature, and moisture. They can change in hue and intensity, and yellows can become pale.

The practice of mass coloring and striving for uniformity likely emerged as a result of industrialization in the late 19th century, when packaged and processed foods became widely available, according to Hisano.

“Mass production and industrialization required easier, more convenient ways of making food, and using coal-tar dyes was one of the solutions for creating more standardized food products,” Hisano told The Epoch Times.

Since packaged foods lose freshness, they may lose color or look less natural. So previously, some companies would add compounds such as potassium nitrate and sodium sulfites to products such as meats to preserve their color. These compounds were relatively harmless.

More lurid examples include toxic metals such as lead used to color cheese and candies. Copper arsenate was added to pickles and old tea to make them look green and fresh, and reports of deaths resulted from lead and copper adulteration.

Dye companies started producing synthetic food dyes in the 1870s. Food regulation began in the 1880s. The Bureau of Chemistry, a branch of the Agriculture Department that would later become the Food and Drug Administration (FDA), looked into food adulteration and modification.

Dairy products such as butter and cheese were the first foods authorized by the federal government for artificial coloring.

Just as synthetic food dyes are a prime target of current Health Secretary Robert F. Kennedy Jr. and FDA Commissioner Martin Makary, they weren’t popular with Bureau of Chemistry head Harvey Wiley, who wrote in 1907, “All such dyeing materials are reprehensible, both on account of the danger to health and deception.”

Despite Wiley’s criticisms, by the time his book “Foods and Their Adulteration” was written, practically all the butter on the market was artificially colored.

“The object of coloring butter is, undoubtedly, to make it appear in the eyes of the consumer better than it really is, and to this extent can only be regarded as an attempt to deceive,” Wiley wrote, arguing that if the cows were properly fed during winter, they would naturally produce butter of the appealing yellow shade.

“The natural tint of butter is as much more attractive than the artificial as any natural color is superior to the artificial.”

The FDA

The previous year, in 1906, Congress passed the Food and Drugs Act, prohibiting the use of poisonous or dangerous colors in food. The FDA was formed on the same day the bill was made into law.

After the prohibition, the FDA approved seven synthetic food dyes—most of which would be banned in the 1950s after new animal studies indicated their toxic effects.

However, the FDA has always given greater scrutiny to synthetic dyes than to natural ones. Synthetic food dyes must be given an FDA certification before they can be used, but there is no requirement for natural dyes. While the FDA regulates synthetic dyes as a food additive, natural dyes can be regulated as generally recognized as safe, which is a less stringent authorization procedure.

In 1938, new laws were passed requiring all food dyes, whether synthetic or natural, to be listed on product labels.

By the 1950s, as oil and gas replaced coal as the main sources of energy, food dyes were no longer made with coal tar derivatives; they were made with petroleum-based compounds instead.

These new petroleum-based food dyes are considered very similar in composition and chemistry to their earlier coal tar counterparts, food scientist Bryan Quoc Le told The Epoch Times.

“Petroleum is cheaper, safer, and available in greater quantities,” he said.

The use of synthetic food dyes has been steadily increasing every decade. Data based on FDA dye certification suggest that food dye consumption has increased fivefold since 1955.

A 2016 study estimated that more than 40 percent of grocery store products that were marketed to children contain artificial colors.

Cancer Concern

By the time Wiley became the first head commissioner of the FDA, experts were in contention over which food dye was riskier than the other. Over the following decades, dyes that were initially approved were gradually whittled down to the six remaining dyes of today.

In 1950, many children fell ill after eating Halloween candy containing Orange No. 1, a synthetic food dye. Rep. James Delaney (D-N.Y.) began holding hearings that prompted the FDA to reevaluate all approved color additives.

The hearing also led to the passing of the Delaney Clause, which prohibits the FDA from approving any food additive that can cause cancer in either humans or animals.

Orange No. 1 and several other approved dyes were removed after evidence of animal carcinogenicity.

The Delaney Clause was what prompted the removal of Red No. 3 in January under the Trump administration.

Professor Lorne Hofseth, director of the Center for Colon Cancer Research and associate dean for research in the College of Pharmacy at the University of South Carolina, is one of the few researchers in the United States studying the health effects of synthetic food dyes.

These dyes are xenobiotics, which are substances that are foreign to the human body, and “anything foreign to your body will cause an immune reaction—it just will,” he told The Epoch Times.

“So if you’re consuming these synthetic food diets from childhood to your adulthood, over years and years and years and years, that’s going to cause a low-grade, chronic inflammation.”

Hofseth has tested the effects of food dyes by sprinkling red, yellow, and blue food dyes on cells in his laboratory and observed DNA damage. “DNA damage is intimately linked to carcinogenesis,” he said.

His research showed that mice exposed to Red No. 40 through a high-fat diet for 10 months developed dysbiosis—an unhealthy imbalance in gut microbes and inflammation indicative of damaged DNA in their gut cells.

“This evidence supports the hypothesis that Red 40 is a dangerous compound that dysregulates key players involved in the development of [early-onset colorectal cancer],” Hofseth and his colleagues wrote in a 2023 study published in Toxicology Reports.

The mechanism of how food dyes cause cancer remains to be elucidated.

Hofseth speculates that the biological effects of red and yellow dyes may be attributed to the fact that they are what’s known as azo dyes. The gut hosts bacteria that can break down azo compounds into bioactive compounds that may alter DNA. Hofseth said he believes that if these bioactive compounds impair the gut, they may also contribute to the behavioral problems reported in some children after consuming food dyes.

Behavioral Problems

While the link between food dyes and cancer may remain elusive, the link between food dyes and behavioral problems in some children is much more accepted.

Rebecca Bevans, a professor of psychology at Western Nevada College, started looking into food dyes after her son became suicidal at the age of 7.

Read the rest here…

Tyler Durden

Fri, 05/16/2025 – 20:00