China Q1 GDP Comes In Stronger Than Expected As March Data Stumbles Amid Covid Lockdowns

Overnight, China reported stronger than expected Q1 GDP (driven in no small part by the recent surge in coal use much to the anger of fakenvironmentalists everywhere), offset however by disapponting March data as the recent lockddowns weighed on outlook.

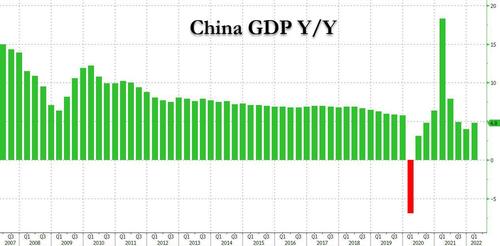

China’s gross domestic product rose 4.8% compared with the same period a year earlier, after expanding 4% in the final three months of 2021. On a quarter-on-quarter basis, GDP grew 1.3%, down from 1.6% in the first quarter. Analysts had projected gains of 4.2% year on year and 0.6% quarter on quarter as Covid outbreaks have increased, leading authorities to largely seal off the financial hub of Shanghai.

“The complexity and uncertainty of the environment at home and abroad has increased, and economic development is facing more difficulties and challenges,” Fu Linghui, a spokesman for the National Bureau of Statistics, said Monday.

However, data for the first three months will not capture the full extent of recent events in Shanghai, which since late March has suffered China’s most severe citywide lockdown since the emergence of coronavirus in Wuhan. Analysts at Nomura last week estimated that 45 cities responsible for about 40 per cent of China’s GDP were under complete or partial lockdowns, and said the country was at “risk of recession”.

Tommy Wu, lead China economist at Oxford Economics, suggested that the 4.8% GDP increase “mainly reflects the growth seen in the official January-February data before the weakening in economic activities in March”. He added: “The central government is now trying to balance minimising disruption against controlling the latest wave of Covid infections, but the disruption is likely to last for weeks and will weigh on activity in April and into May, if not longer.”

And sure enough, the most recent data was much uglier: retail sales, retail sales – a measure of consumer spending – fell 3.5% in March — their first year-on-year fall since July 2020 and worse than a projected 3% decline — and down from a 6.7% increase in the first two months of the year as lockdowns kept people indoors and shut stores to counter the country’s worst coronavirus outbreak in more than two years. In the same month, the official unemployment rate rose to 5.8 per cent, the highest reading in almost two years and the largest one-month increase since early 2020, when China was grappling with the initial outbreak of Covid-19 in Wuhan.

In contrast to the sudden weakness in consumer spending, industrial production, which was a big driver of China’s initial recovery from the pandemic in 2020, added 5 % year on year in March (above the 4.0% expected), but slowing from the 7.5% year-on-year increase in the January-February period. Recent trade data show Chinese imports falling in March for the first time in almost two years as export growth slowed. Data showed factory output also weakened last month as restrictions thinned workforces and snarled up supply chains. At the same time, fixed asset investment rose 9.3% in the first three months of 2022 compared with the same period last year.

Home sales by volume plunged 25.6% in the first quarter compared with a year earlier, while new construction starts measured by floor area dropped by 17.5%. Both of those declines were sharper than in the first two months of the year.

Fu Linghui, a spokesperson for the National Bureau of Statistics, said that “the operation of the economy was generally stable” but pointed to “frequent outbreaks” of Covid in China and an “increasingly grave and complex international environment”, adding that “the country is facing recurring waves of the pandemic in many places and its impact on the economy is increasing.”

As the FT notes, the data will heap greater pressure on President Xi Jinping’s government, which has reaffirmed its commitment to a zero-Covid policy despite the mounting costs and disruption across the country’s biggest cities. In March, the manufacturing hub of Shenzhen was locked down and in the same month the north-eastern city of Jilin was also closed off as part of an approach that has since spread across many other cities.

The lockdowns came at a precarious moment for China’s economy following a debt crisis in its real estate sector and a wider loss of momentum. The government has targeted growth of 5.5 per cent in 2022, its lowest in three decades.

Yet even before the outbreaks of the Omicron variant gathered pace, China’s economy had been hit by a real estate crisis centerd on indebted developer Evergrande that spread across the property sector.

In a sign of the lingering effects of that crisis, new housing starts for apartments declined 20% in the first three months of the year. Steel and cement production fell 6 and 12%, respectively, in the same period.

In addition to its lower annual growth target, the government has also embarked on monetary easing, which has included cutting crucial lending rates for the first time since 2020 despite a previous push to reduce leverage. In response to the slowdown, on Friday, the People’s Bank of China reduced the reserve requirement ratio for banks by 25 basis points in an effort to inject liquidity into the financial system.

Xi, who is this year seeking an unprecedented third term in power, has promoted a “common prosperity” campaign designed to reduce inequality. But lockdown measures now dominate the country’s economic trajectory and have stoked anxiety over supply chain disruptions.

Li Keqiang, China’s premier, has cautioned repeatedly in recent weeks of economic risks, following a warning from Xi in March of the need to minimise the economic impact of Covid policies.

That said, restrictions in Shanghai, a city of 25 million people, have started to ease somewhat after caseloads ebbed, though the city remains under tight control. In Jilin, authorities have declared victory after an extended lockdown. But public-health measures are beginning to tighten elsewhere, highlighting the difficulty of containing the fast-spreading Omicron variant of the virus and the risk of sporadic lockdowns damping economic activity throughout the year.

As the WSJ adds, localized lockdowns are being newly imposed, expanded or extended elsewhere in the country, including the northern industrial city of Taiyuan, the southern megacity of Guangzhou and again in Shenzhen. Forty-five Chinese cities with a combined 373 million people had implemented either full or partial lockdowns as of Monday, a sharp increase from 23 cities and 193 million people a week earlier, according to a survey by Nomura. The 45 cities account for more than one-quarter of China’s population and roughly 40% of the country’s total economic output.

Economists expect Beijing to enact more stimulus measures in the coming months in an effort to hit the 5.5% GDP target. China’s central bank said Friday it would release billions of dollars worth of liquidity to encourage bank lending, though it kept benchmark interest rates unchanged, while a meeting of top officials chaired by Premier Li Keqiang this week teed up plans to bail out industries hit hard by the pandemic such as retail and hospitality and accelerate big construction projects, according to state media.

The CSI 300 index of Shanghai- and Shenzhen-listed stocks fell about 1% on Monday after the data release. Banks were among the worst performers as lenders faced the prospect that policy easing to cushion the economic blow of lockdowns might hurt profits.

“We definitely think that Chinese policymakers are willing to make sure they reach their growth targets,” said Jean-Charles Sambor at BNP Paribas Asset Management.

Tyler Durden

Mon, 04/18/2022 – 07:01